| Lesson 2 | Designing reusable classes is challenging |

| Objective | Learn the problem design patterns solve and how to apply them to build reusable classes. |

Challenges When Designing Reusable Classes

“Code reuse” is often framed as just subclass and override. In practice, reuse fails when classes are tightly coupled to concrete implementations, hidden assumptions, or a single workflow. The GoF patterns offer proven ways to separate roles from implementations and to compose behavior flexibly in languages like Java and C++.

Why Reuse Is Hard (and Common Failure Modes)

- Context coupling: Classes hard-wire environment details (I/O, threads, clock, DB) instead of accepting them as dependencies.

- Inheritance overuse: Deep hierarchies encode variability in type trees; small requirement shifts ripple through many subclasses.

- Leaky abstractions: Public APIs expose internal state/format, preventing safe changes.

- Rigid construction: Callers can’t swap strategies, policies, or collaborators at runtime.

- Insufficient contracts: No clear pre/postconditions or invariants; reuse breaks on edge cases.

- Portability and versioning: Platform/compiler differences and API changes without clear deprecation paths.

- Concurrency surprises: Shared mutable state without thread-safety guidance or immutability.

How Design Patterns Help

Patterns make variation explicit and localize change:

- Strategy / State: Encapsulate algorithms or modes behind interfaces; switch behavior without subclass explosion.

- Factory Method / Abstract Factory: Create families of related objects without binding to concrete classes.

- Adapter / Facade: Decouple your API from legacy or complex subsystems while keeping a clean surface.

- Decorator / Composite: Compose behavior and structure at runtime instead of hardcoding cases.

- Iterator / Observer: Separate traversal and notification from the subjects they operate on.

A Practical OO Workflow for Reusable Designs

- Capture use cases and variability: Identify actors, responsibilities, and where behavior must vary.

- Define interfaces first: Model roles and contracts (preconditions, postconditions, invariants) before picking classes.

- Prefer composition: Inject collaborators (strategies, policies, data sources) via constructors or setters.

- Prototype, then refactor with patterns: Build a simple, working slice; refactor hotspots into patterns as variability emerges.

- Stabilize APIs: Add tests, examples, and deprecation notes; document thread-safety and error semantics.

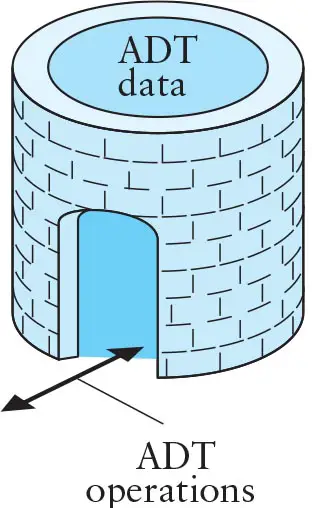

Abstract Data Types, Interfaces, and Contracts

An Abstract Data Type (ADT) defines what you can do-its operations and guarantees-without exposing how it’s implemented. Classes (Java/C++) are a common way to implement ADTs: keep representation private, expose a minimal, coherent set of operations, and enforce invariants through method contracts.

Mini Examples: ADT + Contracts

Java - a minimal Stack ADT (composition-friendly, no leaks of representation):

// Pre: element != null

// Post: size() == oldSize + 1

public interface Stack<T> {

void push(T element);

// Pre: !isEmpty()

// Post: returns last pushed element; size() == oldSize - 1

T pop();

T peek(); // Pre: !isEmpty()

boolean isEmpty();

int size();

}

C++ - strong RAII and clear ownership (no exposure of internals):

class IntStack {

public:

void push(int v); // pre: true; post: size == old_size + 1

int pop(); // pre: size > 0; post: size == old_size - 1

int top() const; // pre: size > 0

bool empty() const noexcept;

std::size_t size() const noexcept;

private:

std::vector<int> data_; // representation hidden (ADT boundary)

};

Checklist: Making a Class Reusable

- Small, coherent API: Names reflect behavior; no representation leaks.

- Composition first: Inject policies/strategies; avoid subclass-only extension.

- Clear contracts: Pre/postconditions, invariants, error semantics, and edge cases.

- Thread-safety notes: Immutable by default or documented synchronization policy.

- Dependency boundaries: Abstract I/O, time, and external services behind interfaces.

- Tests and examples: Unit tests cover behavior; provide minimal usage snippets.

- Versioning: Semantic versioning, deprecations, and migration notes.

- Docs that scale: One-page overview + reference; link to relevant GoF patterns.

Subclass: A class derived from another, inheriting its interface and (optionally) behavior.

Abstract Data Type (ADT): A type defined by its observable behavior (operations and contracts), not its representation.