| Lesson 7 | Singleton: consequences |

| Objective | Discuss and Consider the Effects of using a Singleton. |

Consequences of the Singleton Pattern

The Singleton pattern looks deceptively simple: “one instance plus a global access point.” The real engineering work is understanding the consequences—the tradeoffs that show up in real codebases: lifecycle boundaries (process vs. distributed), concurrency, hidden dependencies, testing friction, and evolving architecture.

In this lesson we review the most important positive and negative consequences, and how modern teams mitigate the risks while preserving the legitimate benefits of “a single shared instance.”

Positive consequences

-

Controlled access to a shared service

When exactly one coordinator is required (for example, a print spooler, a window manager, or a process-wide metrics registry), Singleton provides a single control point. The access method can enforce policies (authorization, throttling, queuing) before returning the instance. -

Reduced duplication of expensive initialization

When object creation is expensive (loading configuration, warming caches, opening device handles), Singleton avoids repeated work. This is most valuable when the instance is used broadly and has a stable lifecycle. -

Centralized consistency

A Singleton can ensure a consistent view of a resource across the runtime boundary: the same configuration snapshot, the same registry entries, the same cache reference, the same instrumentation provider.

Negative consequences

-

Hidden dependencies and tight coupling

A direct call likeFoo.getInstance()hides the dependency. Over time, the codebase can become difficult to refactor because many classes implicitly depend on the Singleton. This is one reason modern teams prefer dependency injection or explicit composition. -

Global mutable state risks

If the Singleton holds mutable state, it becomes a shared global state container. That can produce surprising side effects, order-dependence, and difficult debugging—especially as the number of clients grows. -

Unit testing friction

Tests become harder when state persists across test cases or when you cannot substitute a fake implementation. Workarounds (reset hooks, reflection access, test-only setters) often add additional complexity and can weaken encapsulation. -

Concurrency hazards

In multithreaded systems, naive lazy initialization can create multiple instances or publish a partially-constructed object. Adding synchronization can fix correctness but may introduce contention or subtle performance regressions. -

“Singleton” does not mean “single globally”

In a distributed deployment, each process can have its own Singleton instance. If you need “only one active coordinator” across machines, you need a distributed mechanism (leader election, distributed locks, database constraints), not an in-process Singleton.

Controls access

One positive consequence frequently cited in GoF discussions is that Singleton can control access to its sole instance.

Because the instance reference is private, all access flows through a public method (such as getInstance()).

That method can apply policy:

limiting concurrent use, counting callers, delaying access until the system is ready, or returning a proxy/wrapper.

This is not unique to Singleton—any well-designed class can enforce access rules. The distinctive difference is that Singleton concentrates this access policy into a single, globally reachable entry point.

Thread safety and the legacy synchronized accessor

Many older Java examples use a synchronized accessor to make lazy initialization safe:

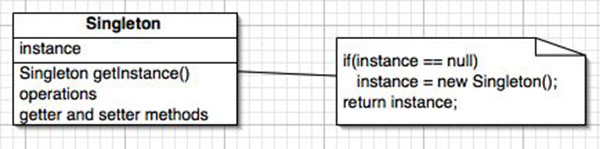

public class Singleton {

private static Singleton instance;

protected Singleton() { }

public static synchronized Singleton getInstance() {

if (instance == null) {

instance = new Singleton();

}

return instance;

}

}

This works, but it has a consequence: every call to getInstance() pays synchronization overhead.

In modern Java, teams often prefer alternatives that keep correctness while reducing contention,

such as the initialization-on-demand holder idiom or enum singletons.

Subclassing: flexibility, but also complexity

GoF mentions that a Singleton can be subclassed so that an application can be configured with different behavior at runtime. This can be useful, but it introduces complexity because you must ensure that the “single instance” contract is not violated and that clients are not forced into unsafe casts.

In modern systems, the more common way to achieve “swap behavior” is: define an interface and let the composition root or DI container supply a single implementation instance. That preserves a single shared instance while avoiding inheritance constraints and class casting risks.

If you do support subclassing, document the boundary clearly: “one instance of the base type” vs. “one instance per subclass” are different semantics and lead to different behaviors.

Modern alternatives that reduce negative consequences

Many of Singleton’s benefits come from “single shared instance,” not from “global access.” Modern architecture often keeps a single instance while avoiding the global accessor:

- Dependency Injection (preferred): container creates one instance and injects it into consumers.

- Composition root: top-level assembly constructs a single instance and passes it explicitly.

- Stateless utilities: if there is no state, use pure functions instead of a Singleton instance.

These options keep dependencies explicit, improve testability, and reduce the “global state” smell, while still supporting a single shared service when it is truly required.

Singleton Consequences - Quiz

Singleton Consequences - Quiz